Inflation is Multiple Taxation

The Hidden Cost of Taxing Illusory Gains

You're likely already familiar with the concept of inflation: the steady erosion of a currency's purchasing power due to rising prices. But one of the most underappreciated and insidious consequences of inflation is how it interacts with the tax code.

Because governments tax nominal gains (denominated in fiat) rather than real (inflation-adjusted) gains, they are effectively imposing two forms of taxation upon citizens: first through inflation itself by siphoning your spending power, and then again through taxes on effectively fake paper profits. Many tax credits, brackets, and benefit thresholds are not fully or frequently adjusted for inflation, meaning taxpayers often face higher effective burdens even when their real economic standing has not improved. This collection of effects constitutes a systemic and silent double (or even triple) taxation on citizens.

The Mirage of Capital Gains

To illustrate how inflation leads to phantom gains, consider a basic example: an investor buys an equity or commodity for $1,000. Over time, and ONLY due to 10% inflation, the asset rises in price to $1,100. This increase merely reflects the asset keeping pace with the devaluation of money. The investor has experienced no real gain in purchasing power, only a nominal increase that mirrors inflation. However, under the tax code, selling the asset for $1,100 triggers a $100 capital gain, which is taxed as though it were a real profit. The investor now owes tax on "income" that doesn't actually exist in real terms.

Note that this example is not merely theoretical. At time of writing, halfway through the year, the US Dollar has lost nearly 10% of its value in 2025.

The Stealthy Sneak of Bracket Creep and Shrinking Benefits

The injustice does not stop at capital gains. A broader and more insidious effect of inflation lies in how tax brackets, deductions, credits, and means-tested benefits are treated. Only some of these thresholds are adjusted automatically or even regularly for inflation, and even those that are adjusted are done so in a questionable fashion. This phenomenon is known as bracket creep.

As wages and asset values rise nominally to keep pace with inflation, taxpayers can be pushed into higher tax brackets even though their real income has not increased. For instance, a worker who receives a 5% raise in a year with 5% inflation is no better off in real terms, yet may end up in a higher tax bracket, losing more of their income to taxes. This effect is subtle but pervasive.

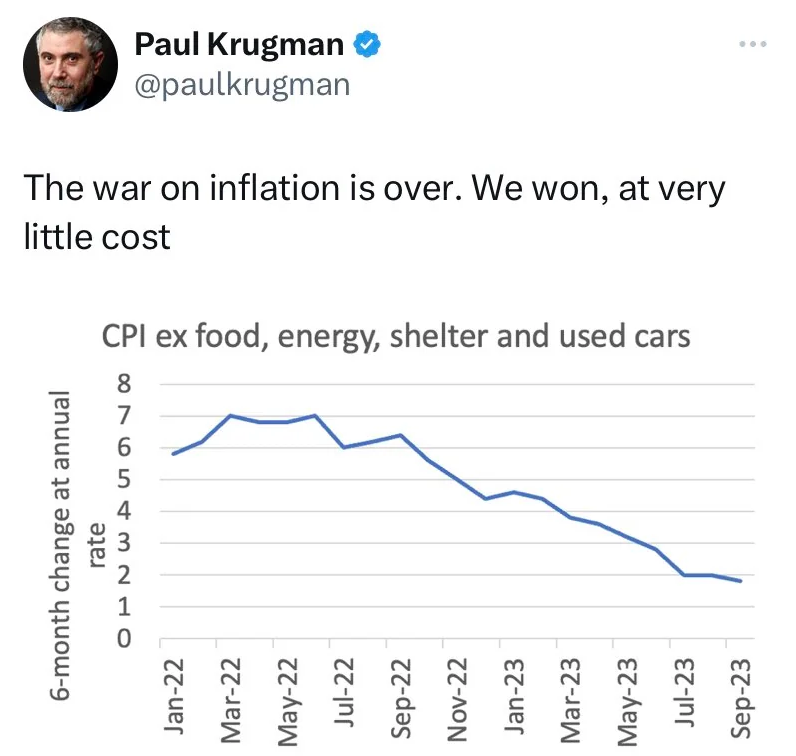

Every year, the IRS adjusts more than 40 tax provisions for inflation. The IRS uses the Consumer Price Index (CPI) to adjust the value of the parameters. It does this by taking the tax parameter’s base value and multiplying it by the current year’s CPI and dividing it by the base year’s CPI. But there's a catch: CPI is a laughable manipulated metric that is regularly being changed. It makes one wonder: who benefits from these changes?

Pre-1983, mortgage costs were in the CPI as were car payments pre-1998. Now, price indexes do not include borrowing costs. Thus, when interest rates jumped last year, official inflation did not fully capture the effects it would have on consumer well-being. 4/N pic.twitter.com/xQc2bvpdYI

— Lawrence H. Summers (@LHSummers) February 27, 2024

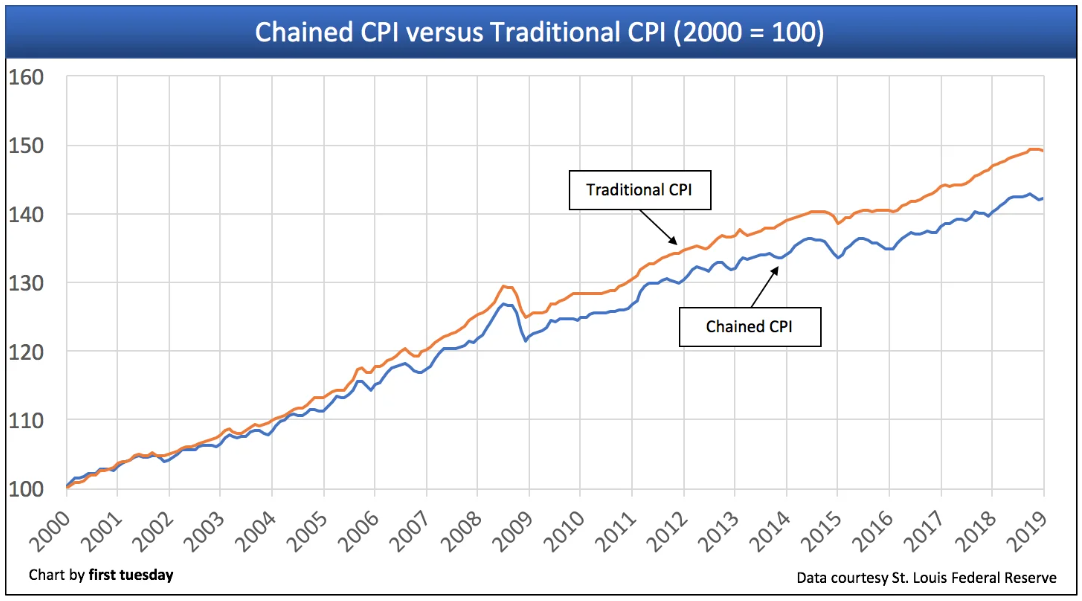

The CPI is not the only way to adjust tax parameters. Tax brackets could be adjusted in a number of ways including average wage growth (as Social Security brackets are currently adjusted) or the Chained CPI, which is a different method of measuring inflation.

The choice of adjustment, albeit an obscure public policy, is impactful for taxpayers. It could mean higher or lower tax burdens over a long period of time. A U.S. federal law passed in 2017 applied the chain-weighted CPI instead of the primary CPI for adjusting the incremental increases in income tax brackets. But it turns out that by switching to this metric, the increases to tax bracket adjustments will be comparatively smaller each year and the gap between real and nominal value taxed grows wider.

This move to chain-weighted CPI is expected to eventually push more citizens into higher tax brackets, thereby increasing the taxes they owe as the effects of this gap compound over time.

In addition, tax credits and deductions such as the Child Tax Credit, Earned Income Tax Credit, and medical expense deductions often lag behind inflation or are capped without adjustment. Over time, the real value of these credits shrinks, delivering less benefit even as the cost of living rises. Similarly, income thresholds for benefits like food assistance, housing subsidies, or education grants can remain fixed for years, resulting in people losing eligibility simply because of inflation-adjusted pay increases.

This means inflation not only erodes the real value of what individuals earn and save. It can also strip them of tax relief and government support, even when their standard of living remains unchanged.

Compounded Losses

Together, these effects compound the burden on responsible financial behavior. Over the long term, citizens face:

- A silent tax via inflation that devalues their cash and fixed assets.

- A phantom gain taxed as a capital gain, even when there’s no real profit.

- A higher marginal tax rate through bracket creep, without any increase in real wages.

- Reduced tax credits and benefits, simply for keeping up with inflation.

This system penalizes not only investors but also wage earners, retirees, and anyone relying on fixed incomes or government assistance. Over decades, these distortions add up to a massive wealth transfer away from ordinary citizens and toward the government, without any explicit legislation to raise taxes.

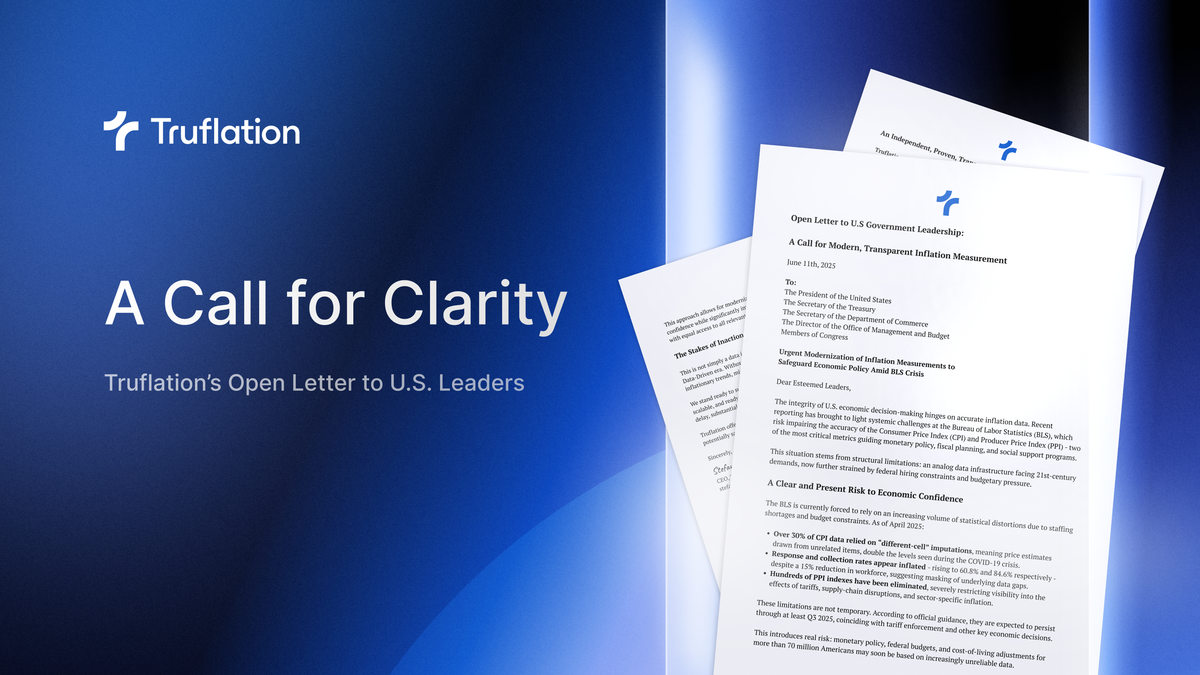

A Case for Reform: Indexing the Tax Code to Reality

To address these distortions, tax policy must account for inflation more rigorously and comprehensively. Capital gains should be indexed to an accurate measure of inflation, ensuring that only real increases in wealth are taxed. In addition, tax brackets, deductions, and benefit thresholds should be adjusted annually in line with inflation, using accurate and responsive metrics. There is indeed great cause for concern that the US Government's methods of measuring inflation are becoming increasingly unreliable. These inaccuracies are sure to result in many downstream effects by all the agencies that make decisions based upon them, and thus upon all the citizens who are affected by agency policies.

While some jurisdictions attempt partial inflation indexing, these efforts are often incomplete or politically manipulated. A principled and consistent approach would restore fairness by ensuring that the tax system targets actual income and wealth rather than statistical illusions.

In Summary

Inflation is more than a macroeconomic challenge; it is a multiplier of stealthy taxation. By eroding the value of money while the tax code continues to assess nominal incomes and gains, inflation becomes a tool of double taxation. When this is combined with tax brackets, credits, and benefits that fail to adjust accordingly, the result is a system that disproportionately squeezes citizens from all walks of life. It is a slow, quiet betrayal of financial prudence and long-term planning. Reforming the tax system to account for inflation is a necessity for preserving fairness, transparency, and economic integrity in an era of persistent currency devaluation.