A Treatise on Bitcoin Block Space Economics

Note: if you're prefer to consume this essay in video presentation formation, check out my keynote here:

Nobody:

Absolutely no one:

Nary a single bitcoiner:

Me: "let's discuss changing the block size!"

Seven years have passed since the block size wars effectively ended via frustrated big blockers forking off to their own networks. Unfortunately for big blockers, they've ended up in an awkward position.

Bitcoin Cash: despite increasing their max block size to 32 MB, their actual real-world block sizes are smaller than Bitcoin. The lack of adoption has resulted in Bitcoin Cash's exchange rate and hashrate floundering, thus this network is much further from having sustainable fees to pay for thermodynamic security than Bitcoin.

Bitcoin SV: with con men in leading roles of this network, it took "big blocks" to a cartoonishly absurd level. The BSV blockchain is so big that the mere prospect of running a full node is a turn-off not only to individuals, but also to most enterprises. And even more absurdly, despite their high transaction volume the transaction fees are so low that it's arguably less sustainable than Bitcoin Cash.

Bitcoin, it seems, is in the Goldilocks Zone. Blocks are small enough that our full node counts are sustainable, but they're not too large to prevent a fee market for block space from forming, slowly working our way toward sustainable thermodynamic security.

Why Talk about Block Size Now?

The mere fact that nobody is talking about it means that there's very little urgency, drama, and contention around this issue. Many folks who fought on the front lines of the block size wars have effectively retired or moved onto other things. Few wish to reopen old wounds and revisit the trauma from years past. Some of you may recall that I myself had a SWAT team show up at my house as a result of the vitriol and high tensions on social media during the scaling debates! But that's a whole other story.

I've also noticed a disturbing trend of folks who simply state that the block size must NEVER be increased, presumably because they don't want to wade into an extremely nuanced debate. I find such dismissals to be intellectually lazy. "Never" is an extremely long time, and I view Bitcoin as a multi-generational project. This essay will not mention time frames at any point, so if it makes you calmer, feel free to think on the order of decades. If you're an ideological "1 megabyte forever" hardliner, feel free to close your browser tab and go back to X.

Just to spice things up, here's a juicy meme to trigger some folks:

From the conclusion of the Lightning Network whitepaper:

If all transactions using Bitcoin were on the blockchain, to enable 1 billion people to make two transactions per day, it would require 24GB blocks every ten minutes at best (presuming 250 bytes per transaction and 144 blocks per day). Conducting all global payment transactions on the blockchain today implies miners will need to do an incredible amount of computation, severely limiting bitcoin scalability and full nodes to a few centralized processors.

If all transactions using Bitcoin were conducted inside a network of micropayment channels, to enable 7 billion people to make two channels per year with unlimited transactions inside the channel, it would require 133 MB blocks (presuming 500 bytes per transaction and 52560 blocks per year). Current generation desktop computers will be able to run a full node with old blocks pruned out on 2 TB of storage.

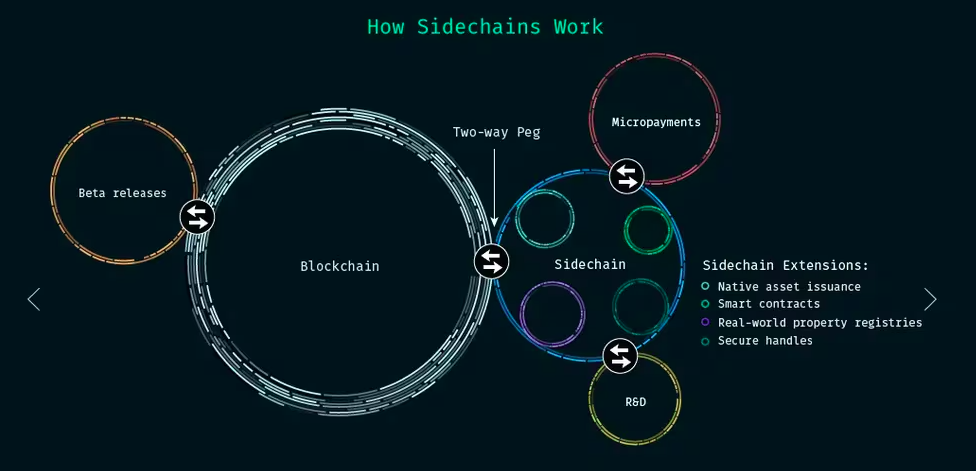

Naturally there are a variety of caveats and assumptions made for the above conclusion, but I recommend zooming out. Lightning Network is arguably the best and currently only sovereign second layer currently available to Bitcoin users without trusting intermediaries. Why should it remain the only such layer in perpetuity? In short: my hope is that we continue to scale Bitcoin into a system that supports a multitude of sovereign second layers. That was the vision first put forth by Blockstream in the seminal 2014 sidechains whitepaper. A vision we have yet to achieve...

The Problem

There's no point discussing potential solutions if we don't agree upon the problem. It took several years of participating in the block size debates before I was able to distill the root disagreement down to a single sentence:

Should Bitcoin optimize for low cost of full system validation or should it optimize for low cost of transacting?

Clearly, the former philosophy won. Thus if we accept the constraint of this philosophy, what would the crux of a future block size debate look like? Perhaps something like this:

How can we maximize the number of people who are able to use Bitcoin without trusted third parties, in a permissionless manner, without disrupting the balance of power and game theory that keep the system sound?

The demand for cheap block space is practically unbounded. If you don't believe me, just look at BSV's blockchain size, which over 11 TB at time of writing. And my own tests 2 years ago when it was 3 TB showed that my benchmark machine couldn't sync a BSV node even in pruned mode.

I think that the problem is one of both finding and maintaining a "Goldilocks Zone" when it comes to on-chain capacity.

If the system is too costly people will be forced to trust third parties rather than independently enforcing the system's rules. If the Bitcoin blockchain’s resource usage, relative to the available technology, is too great, Bitcoin loses its competitive advantages compared to legacy systems because validation will be too costly (pricing out many users), forcing trust back into the system. If capacity is too low and our methods of transacting too inefficient, access to the chain for dispute resolution will be too costly, again pushing trust back into the system.

- Gregory Maxwell, in a 2015 mailing list post

There are a ton of excellent arguments that were made over the years regarding the trade-offs inherent to block size increases; rather than rehash them all I'll refer readers to this list.

There's nothing magical about a 1 MB / 4 MB / 4M Weight Unit block size limit. While having a low block size limit is clearly good for safety, it's very difficult if not impossible to argue that it's an "optimal" limit. After all, some would argue that it's actually too high of a limit!

In addition to the trade-off between cost of transacting and cost of validating the system, there's the issue of thermodynamic security. That is to say: minimizing the cost of on-chain transactions ALSO decreases the amount of revenue miners can expect to collect via transaction fees, which (over the long term) reduces the cost of executing a 51% attack and rewriting recent blockchain history. Stated succinctly:

Maximizing Bitcoin's thermodynamic security in perpetuity necessitates that blocks be full.

Don't Rock the Boat

I was having dinner with Michael Saylor in 2023 and he said something that caught me off guard because I'd never heard anyone make the argument before. While I initially scoffed at his complaint, I've since come to realize that it's a valid concern. What did Saylor say?

"It's unethical to increase the block size because you're depriving miners of revenue."

I do disagree with Saylor regarding his characterization of future block space and transaction fee revenue as an issue of miner property rights but that's a tangent for another day. He does make a good point about the economics of block space and the stakeholder interests of miners.

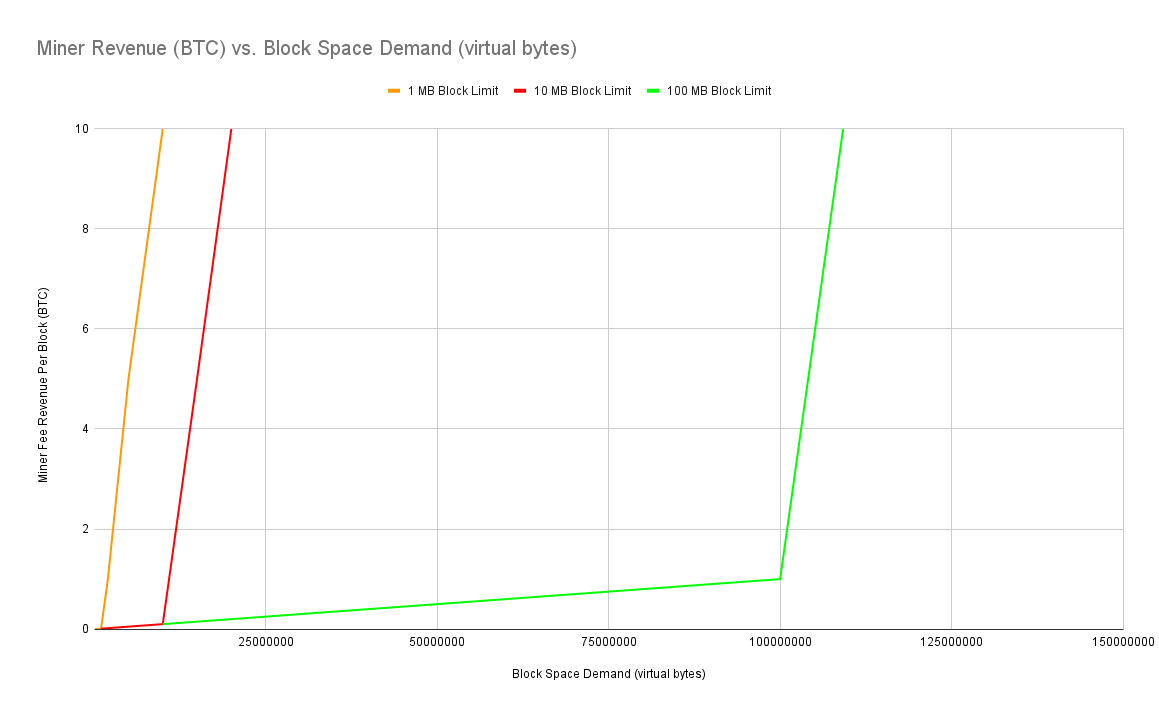

Basically, if you significantly decrease the scarcity of block space then you end up altering the economics of the block space market. If you increase the available block space even a few bytes higher than current demand, you hit a "fee cliff" situation where all of a sudden the minimum fee rate of 1 satoshi per virtual byte will be sufficient to achieve confirmation in the next block. On a related note, there has even been a recent discussion on the developer mailing list about reducing this minimum fee rate even further.

Let me attempt a visual explanation. In short, so long as demand for block space is less than the available supply of block space, miners can only reasonably expect their revenue to grow linearly based upon the minimum relay fee. But as soon as demand exceeds supply, we're off to the races and competition for fee rates tends to make them go parabolic, increasing by orders of magnitude. The next chart is just an rough approximation since you can't perfectly model future demand - there are innumerable variables at play.

However, I'd note that Saylor's argument isn't quite bulletproof. While it's a concern worth keeping in mind, the same argument can be made against any Bitcoin improvement that scales throughput in ways that reduce the need for on-chain transactions. Thus one could attempt to block any scaling proposal under the premise that it's "bad for miners' bottom line." This flip side of such an argument is that more scalability inevitably brings more users to Bitcoin and thus more demand for layer 1 settlement space.

The trick, I think, is to look at the base layer of Bitcoin as a cryptographic accumulator of economic value. It stands to reason that, if sufficient value is created on other layers, it should "trickle down" to the base layer and increase the value of on-chain transactions that are essentially aggregated multitudes of off-chain activities. Explained more simply:

If an on-chain transaction is the settlement of 1,000 off-chain transactions that transferred $100,000+ then it makes sense to pay an on-chain fee of $100 since that's only a 0.1% fee.

The Block Space Economic Cycle

Scarce block space causes people to use precious resources more efficiently. For example, fee pressure resulted in exchanges eventually optimizing their withdrawal processing to create batched transactions with many outputs, which consumes far less block space than using a separate transaction for every withdrawal request. In an ideal world, all exchanges and custodians would use unified on-chain+off-chain invoices for withdrawals. Why? Because nearly half of all on-chain transactions are just sending money from one exchange to another! Those flows of funds could be sent off-chain via high capacity payment channels that exchanges set up with each other... if they went to the trouble to do so.

As a computer scientist I'm painfully aware that despite hardware continually getting faster, software seems to be getting slower. Why is this the case?

- Programmers will use all the resources available to them to create software that works.

- As we build upon the shoulders of giants, our software is becoming ever more complex and bloated because developers simply import 3rd party libraries to accomplish more and more common functions rather than reinventing the wheel.

- Optimizing software is a masochistic task that most developers only undertake if the performance is so poor that the software becomes unusable.

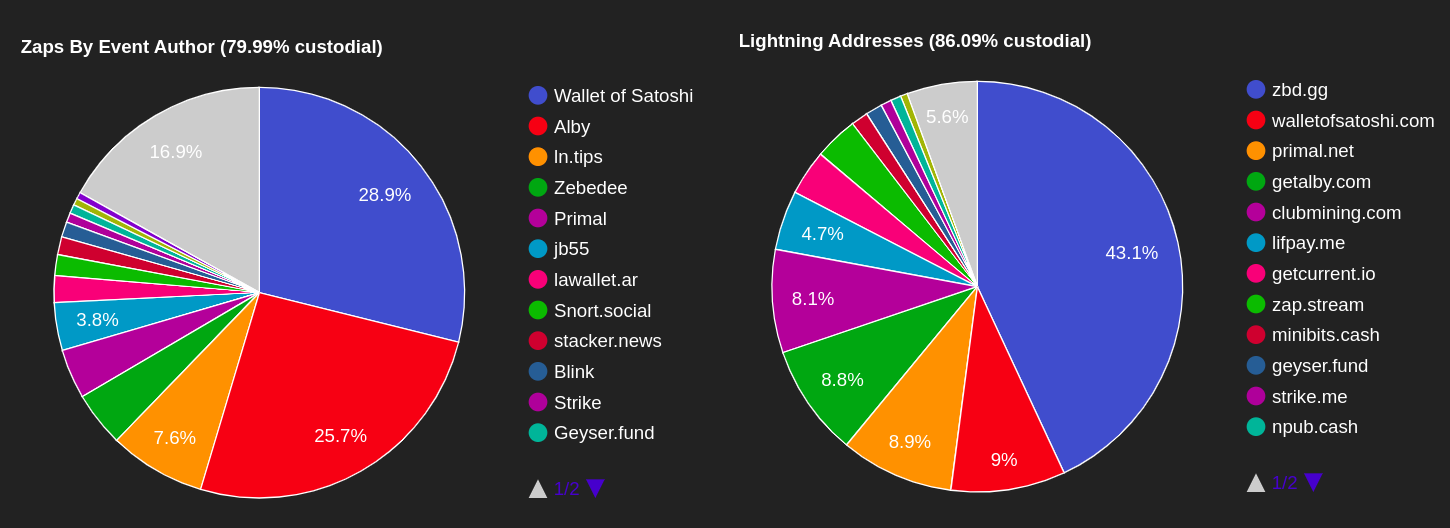

There are also numerous centralization pressures: while small block sizes keep the network of full nodes decentralized, high on-chain fees incentivize using custodians. One could argue that high fees also incentivize using second layer solutions, though I'd argue both are true: they also incentivize using custodial second layer solutions, as we've seen happen with adoption of custodial lightning wallets.

The Price of Sovereignty

If the cost of block space rises too high then it will be a centralizing factor that prices out many self custody use cases, including self custody of second layer solutions.

For example, the minimum viable cost of block space to anchor into a second layer, be it via opening a lightning channel or pegging funds into a sidechain, will depend upon the expected value and fee savings incurred during the lifetime of the funds existing in the second layer.

As such, there's yet another economic balancing act at play here. If the cost of block space is too low then everyone will just transact on chain and perform low economic value actions on chain that have to be stored by every full node for all eternity. On the other hand, if it's too high then people will just transact with bitcoin IOUs issued by centralized issuers because the cost and complexity of using that "off-chain scaling solution" will appear to be zero - of course the true cost is giving up sovereignty. What appears to be preferable is to have enough cost on-chain to incentivize using off-chain solutions for scaling, but not so high on chain that even sovereign off-chain solutions are too costly and thus users get pushed to trusted third parties.

This chart of lightning usage by folks on nostr shows how difficult it is for sovereign software to compete with the convenience of trusted third parties:

Goldilocks Problems

Why is the block size parameter so contentious? Because different folks want to optimize for different things, we have desires and proposals that are all along a wide spectrum of parameters.

On one extreme you've got "micro-blockers" like Luke Dashjr who would like to see the block size reduced.

Then you've got the "pro-ossification" folks / "small blockers" who just want to keep the parameters as they stand today.

Then you've got the "big blockers" who view block space as a "capacity planning" issue and believe that we should strive to always have more "head room" AKA more supply available than demand. In the early days of the scaling debates I was actually in this camp myself due to my background scaling cloud infrastructure. You can read about this perspective from Mike Hearn:

A History of Block Size Proposals

There have been 9 "officially" proposed block size increases, pretty much all of them were made in the 2016 / 2017 era during peak block size debates. All 9 were either rejected or withdrawn. Let's review the proposals and set aside the fact that they are all hard forks that come with a whole other slew of activation issues.

BIP100 - Dynamic Block Size via Miner Vote. A 75% mining supermajority may activate a change to the maximum block size each 2016 blocks. Each change is limited to a 5% increase from the previous block size hard limit, or a decrease of similar magnitude.

My take: clearly ridiculous because it gives miners so much power. Also, at 5% compounded biweekly increases, that could result in annual increases of 250%. That is, we could end up with 50 MB blocks in just 2 years.

BIP101 - Block Size Doubling. Increases block size to 8 MB and doubles it every 2 years for 20 years.

My take: overly simplistic, results in a max block size of 8 GB which is rather absurd and can't be proven to be "safe."

BIP102 - 2MB blocks. A simple, one-time increase in total amount of transaction data permitted in a block from 1MB to 2MB.

My take: seems safe since it's conservative, but it's not a long-term fix. Requires future hard forks to adjust block size as needed.

BIP103 - Increase block size with technological growth of bandwidth: 17.7% per year. The development of a fee market and the evolution towards an ecosystem that is able to cope with block space competition should be considered healthy. This does not mean the block size or its limitation needs to be constant forever. However, the purpose of such a change should be evolution with technological growth, and not kicking the can down the road because of a fear of change in economics.

My take: This is one of my favorite proposals because it actually has rationale behind the rate of increase rather than pulling a nice sounding round number out of a hat. The downsides are that I'm not sure bandwidth should be the sole resource cost taken into consideration, and also it doesn't actually have anything to do with the economics of block space demand.

BIP104 - Automatic adjustment of max block size with the target of keeping blocks 75% full, based on the average block size of the previous 2016 blocks.

My take: I totally get the perspective taken here, as I started off my stance in the block size debates from a "capacity planning" perspective I brought due to my experience running large scale systems. Unfortunately, this perspective is a fail for Bitcoin because by constantly striving to have "overhead" in your capacity, you are guaranteeing that you're effectively aborting any market from forming for block space - fees will always remain at the relay floor of 1 satoshi per virtual byte. Also, this proposal is trivially gameable by miners that can fill their blocks for free.

BIP105 - Miner voting for block size increases via higher difficulty targets. Miners can vote to increase the block size by up to 10% with a hard cap of 8 MB. If a miner votes for an increase, the block hash must meet a difficulty target which is proportionally larger than the standard difficulty target based on the percentage increase they voted for.

My take: this is a novel proposal because it puts an economic cost onto miners; presumably it means they won't vote to increase the block size unless they believe a block size increase would be more profitable than the cost of voting. Downsides to this BIP are that it doesn't account for node operation costs and it still has a hard cap that would likely get hit sooner rather than later, taking us back to square 1. With this proposal the hard cap could get hit in less than 1 year.

BIP106 - Dynamic block size based upon recent block sizes or transaction fees. If more than half of the past 2,000 blocks were more than 90% full, double the max block size. If more than 90% of the past 2,000 blocks are less than 50% full, halve the max block size. Then there's a variation on this logic that also includes looking at transaction fees and only increasing the cap if fees have gone up, and only decreasing the cap if fees have gone down.

My take: this proposal is confusing, especially because it's 2 proposals in one BIP. It's overly complicated and would result in some very wonky behavior.

BIP107 - 3 static block size increases followed by a dynamic algorithm. Increases block size by 2MB every 2 years for 6 years, then every 4 weeks potentially increase the max size by 10% if more than 75% of the past 4 weeks of blocks were more than 60% full.

My take: feels like a lot of magic numbers. Doesn't really do anything with regard to the economics of block space. Similar to BIP100, at 10% compounded quadweekly increases, that could result in annual increases of 250%.

BIP109 - One-time increase in total amount of transaction data permitted in a block from 1MB to 2MB, with limits on signature operations and hashing.

My take: Same as BIP102. Seems safe since it's conservative, but it's not a long-term fix. Requires future hard forks to adjust block size as needed.

Other Systems' Adjustment Mechanisms

The nice thing about the diversity of the cryptocurrency ecosystem is that Bitcoin should be able to learn from the mistakes and successes of other protocols. But have many other protocols even implemented dynamic caps on throughput? The overwhelming majority of networks have never seen enough adoption for their throughput to come anywhere near saturating the default limits.

Bitcoin Cash recently implemented an adaptive block size limit algorithm that you can read about at https://gitlab.com/0353F40E/ebaa/-/tree/main#chip-2023-04-adaptive-blocksize-limit-algorithm-for-bitcoin-cash

Dash has a unique two-tier network with miners and masternodes. It uses a self-funding, self-governing model and can adjust its block size based on network demand. This seems tantamount to a proof of stake vote.

Ethereum has gas limit voting. But then you can have people in leadership positions that campaign for miners to increase their gas limits. For example, see this recent reddit comment from Vitalik Buterin that got turned into media articles. Ethereum also changed their fee market dynamics with EIP-1559.

Monero has an automatic adjustment of BOTH the block size limit and the minimum transaction fee, which you can read about at https://github.com/JollyMort/monero-research/blob/master/Monero Dynamic Block Size and Dynamic Minimum Fee/Monero Dynamic Block Size and Dynamic Minimum Fee - DRAFT.md

Of all the above algorithms, the only one I find interesting is Monero's, because it's truly algorithmic rather than human / voting based, and because it's the only one that's actually economic in nature, ensuring that block size increases don't kill the block space market.

Block Size Concerns That Must be Addressed

We must take care to preserve the key properties of Bitcoin.

The stability of the system must be prioritized above all else. What does that mean? Folks often say "we must keep the system decentralized" but that's fairly worthless for several reasons.

- Decentralization is a spectrum, not a binary attribute.

- Systems can be (de)centralized along many different attributes.

I think the important aspect above all else when thinking about a system's decentralization is the distribution of power among actors in the system. That is to say: a sufficiently decentralized system is one in which the power is not concentrated into a group of entities that is small enough for them to easily coordinate with each other in order to enact changes without rough consensus of the rest of the network.

What is the appropriate security budget for miners? Nobody knows for sure; it's desirable for it to be as high as possible to make it too costly for even nation states to attack. What we can be sure of is that if the revenue collected by miners goes down over a long time frame, so will the hashrate that protects the network against double spends.

We should also take care not to disrupt the balance of power between node operators and miners. Neither should we disrupt the balance of power between individuals and enterprises. In particular, algorithmic block size caps are prone to being gameable by miners, who can "stuff" blocks full of transactions that cost them nothing because they are paying the fees to themselves. I believe there are solutions to this problem, which I'll explore in future posts.

Fee pressure (a robust auction market for block space) is desirable in order to incentivize efficient use of block space, per the earlier meme about block space usage cycles.

Full node safety: one of the greatest dangers of blocks that are too large relative to the current cost of computing resources are denial of service or resource exhaustion attacks. In other words, maliciously crafted transactions and blocks could cause nodes to take an inordinate amount of time to verify them, which could drastically slow down the propagation of blocks throughout the network and give an adversarial miner an unfair "head start" on mining the next block, effecting a sort of 51% attack that doesn't actually require 51% of the network hashrate.

There are several efforts that could help with node operator safety such as the Great Consensus Cleanup to limit worst case block validation https://delvingbitcoin.org/t/great-consensus-cleanup-revival/710

Additionally, we could create a "gas" accounting system for resource use the targets keeping the cost of node operation stable and in line with Moore's law and others. Bandwidth CPU cycles disk I/O disk storage. The downside to this idea is that it would add a bit of complexity to the consensus rules. We learned from Ethereum's gas system that it's possible to accidentally "misprice" certain operations and have them used against the network as a denial of service attack. Bitcoin does currently have the concept of counting signature operations, which could be viewed as a rough "CPU" resource cost. To learn more about this topic, check out Rusty Russell's Great Script Restoration Project:

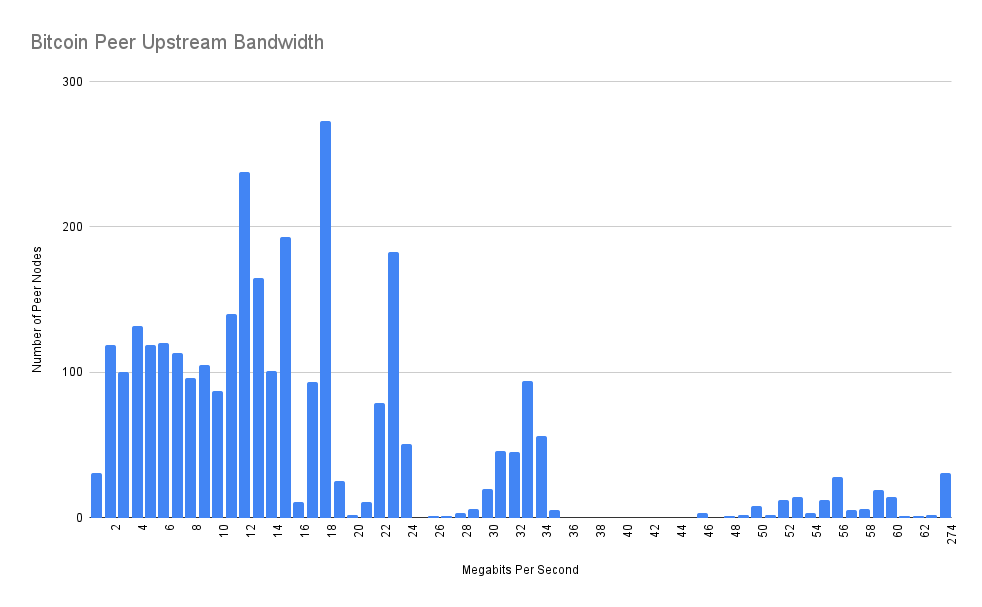

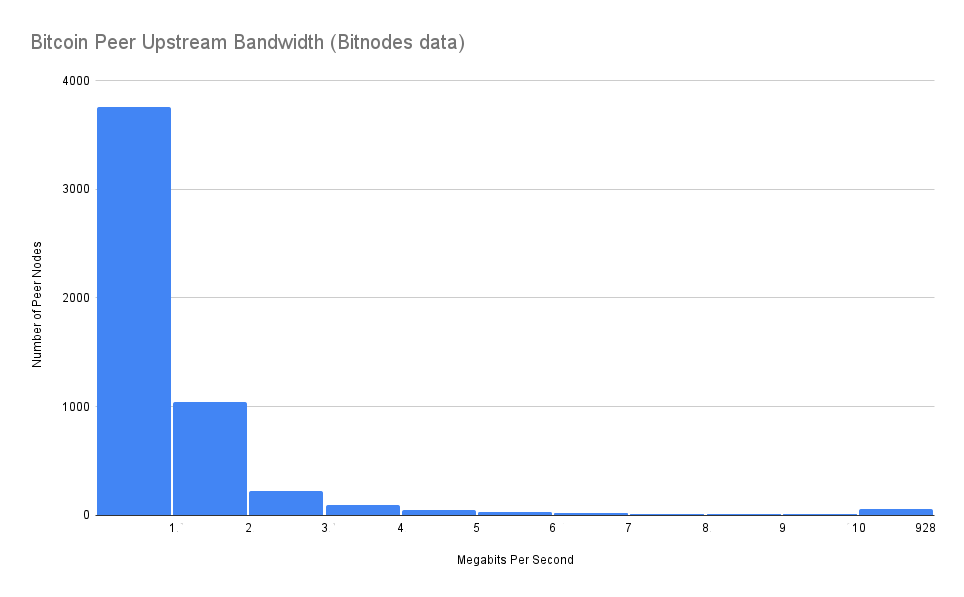

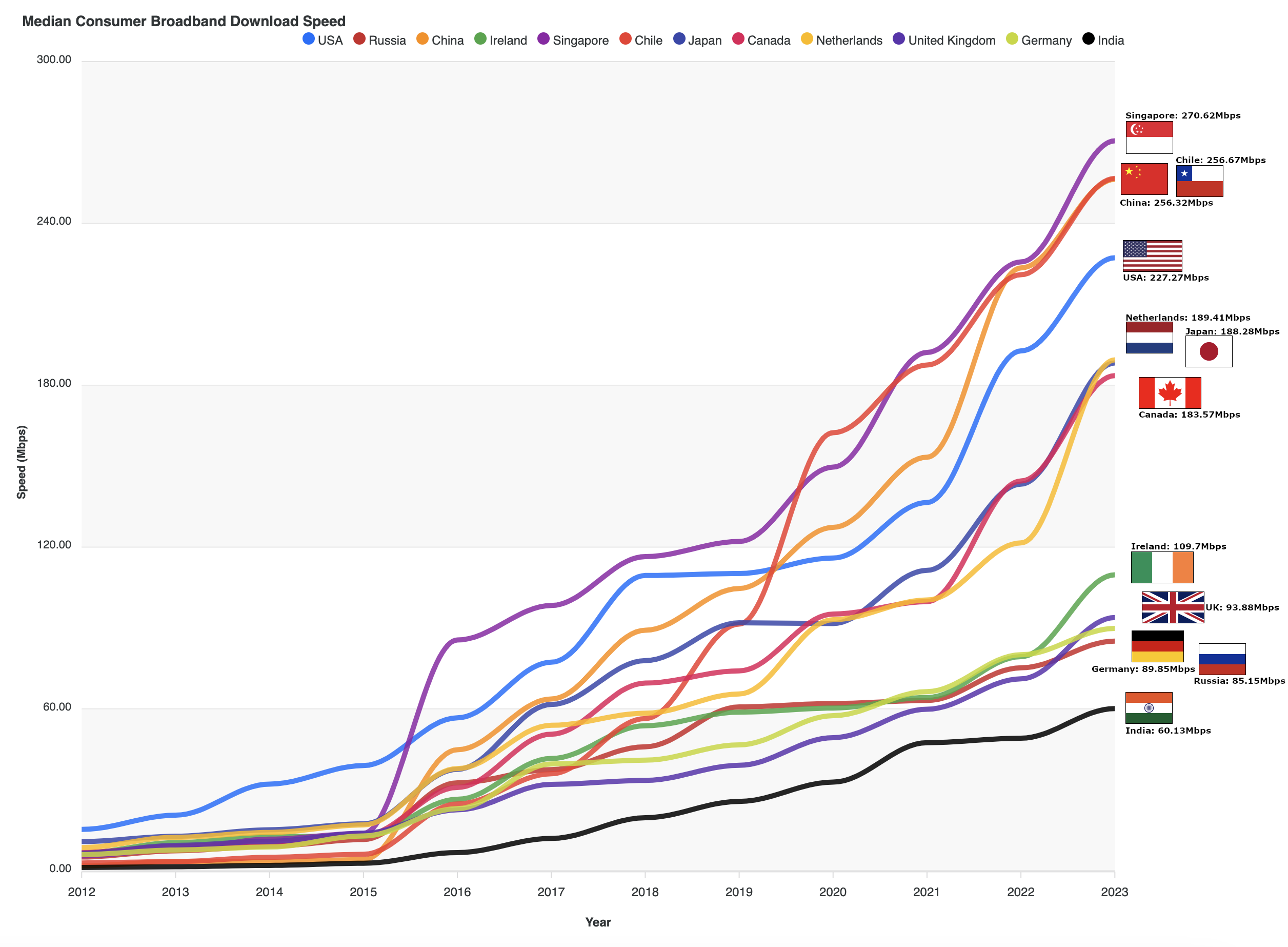

Bandwidth limitations: I think it's uncontroversial to state that it's desirable for full nodes to be run by hobbyist operators on residential internet connections using consumer grade hardware such as laptops, desktops, and Raspberry Pis. It's also preferable that Bitcoin nodes can be operated over the Tor network to allow for stronger privacy.

As such, we should be cognizant that most residential broadband connections are asymmetric in nature - in other words, the upstream bandwidth is far lower than the allowed download bandwidth. This becomes important when you consider that it's desirable for blocks to propagate across the network as quickly as possible. It's also desirable, for improved censorship resistance, for fully validating nodes to be able to run over the tor network.

According to tests I ran in 2022,

Average Peer Speed: 17.3 megabits per second

Median Peer Speed: 12.1 megabits per second

According to Bitnodes' crawler data, upstream bandwidth is even worse!

Average Peer Speed: 2.0 megabits per second

Median Peer Speed: 0.8 megabits per second

Lastly, I think it's desirable to minimize future debates and drama. Bitcoin should be as apolitical as possible and debates over protocol changes that have massive effects on the economics and game theory of the system are incredibly draining. One-off block size changes don't fix the underlying problem. Nobody wants to have to go through another round of block size debates every time a hard cap gets hit.

Technological Progress

Technology is deflationary by nature. That is: the cost of acquiring a certain level of technological resources trends down over time. As technology advances, you get more bang for your buck.

As a result, there are several "laws" that are observations and projections of historical trends. Rather than a law of physics, it is an empirical relationship linked to gains from experience in production.

Moore's Law: the number of transistors in an integrated circuit (CPU / GPU) doubles about every two years.

Nielson's Law: A high-end user's connection speed grows by 50% per year.

Edholm's Law: bandwidth and data rates double every 18 months.

Kryder's Law: magnetic disk areal storage density increases at a rate exceeding Moore's Law.

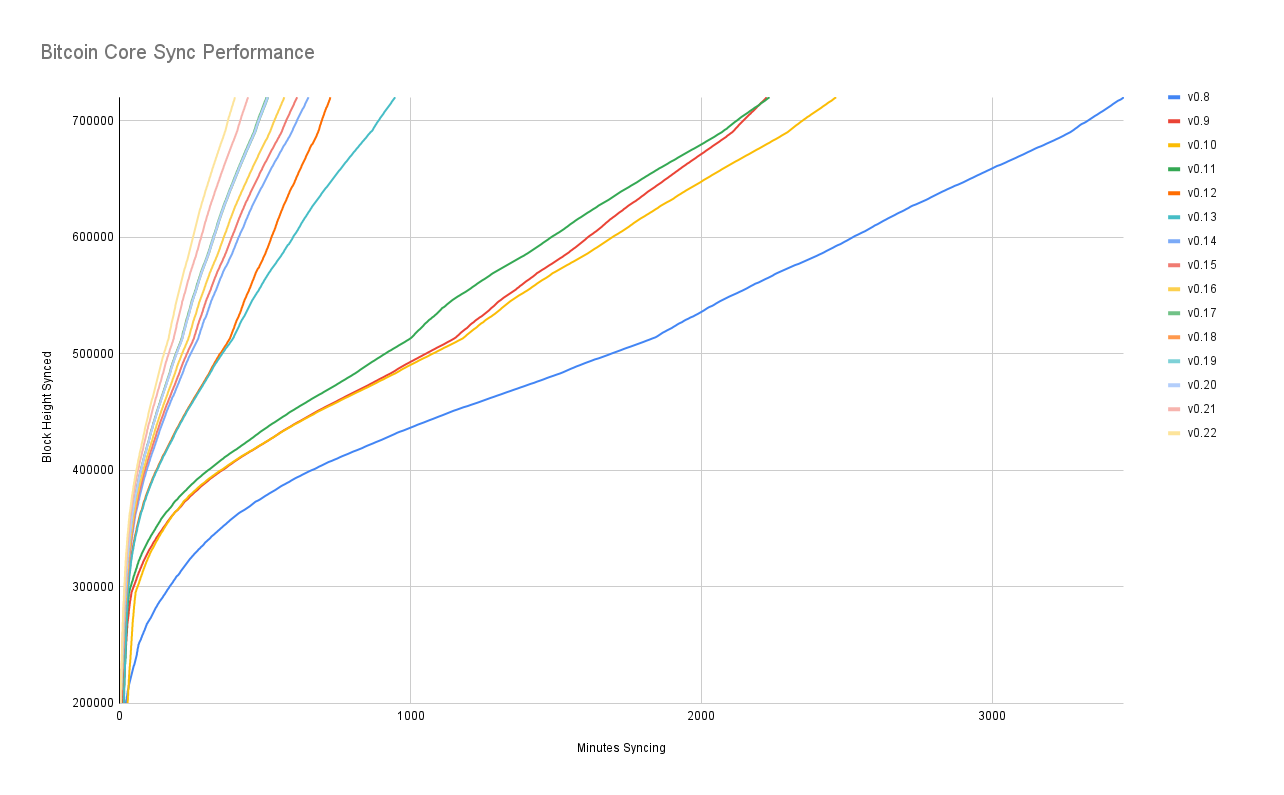

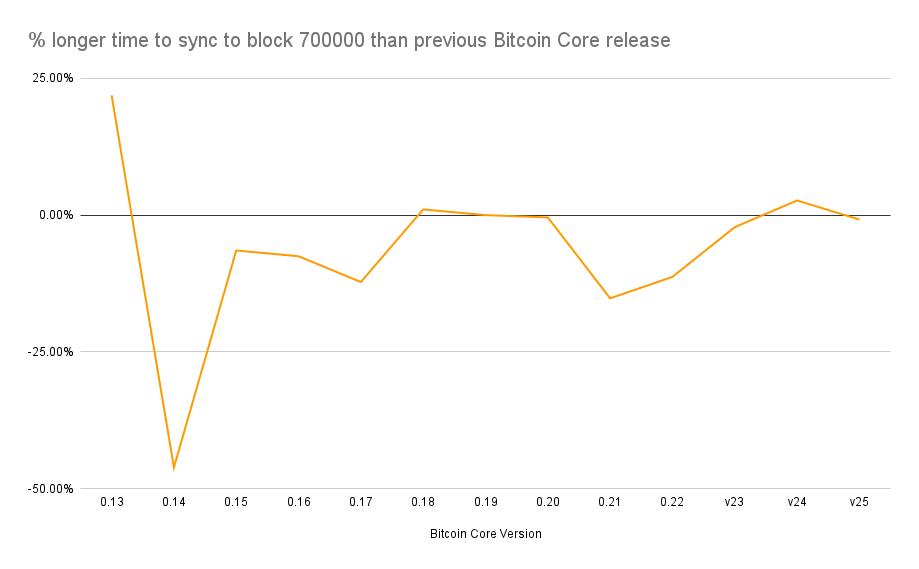

We can also reasonable expect that Bitcoin software will continue to improve from a performance standpoint. Take, for example, the benchmarking tests I performed across many versions of Bitcoin Core.

Put differently, if we look at the delta in sync times to a given block height of 700,000 we can see that the average Bitcoin Core release includes about a 5% performance increase. There are 2 releases per year, so about 10% faster per year. Though the blockchain is currently growing at 25% per year, so it's a struggle to keep up with the additional data that must be verified.

Metcalfe's Law states that the financial value or influence of a telecommunications network is proportional to the square of the number of connected users of the system. As such, anyone who holds BTC is incentivized to see as many people as possible adopt bitcoin in order to increase its value.

Block Size Dynamics

Remember that the block size cap only prescribes the maximum size block a miner can mint. They will presumably have other limitations at play, such as ensuring that their block propagates across the network quickly in order to prevent orphan races.

Block size is very important with regard to layer 2 tech. There's another Goldilocks Zone at play here: it's desirable for blocks to be small enough that users of layer 2 technology can run a full node to ensure that their off-chain counterparties aren't trying to cheat them. It's also desirable for blocks to be small enough to encourage the use of layer 2 technologies. On the flip side, if blocks are too small then it will price out the average user from using layer 2 technology in a sovereign / self custodial fashion and push them into trusted third party custodians.

In order to change the block size without creating a controversial fork crisis, all the major stakeholders must be appeased that it is in their best interests to support one specific proposal.

- Miners

- Exchanges

- Businesses

- Individual holders

- Institutional holders

- Bitcoin client engineers

An important thing to keep in mind here is which stakeholders can impose costs upon other stakeholders as a result of their decisions:

- Miners can impose costs upon all other stakeholders (who run nodes) by increasing their production of block space.

- Protocol developers can impose costs upon all other stakeholders by increasing the allowed production of block space.

- Businesses and exchanges can impose costs upon node operators by promoting use of on-chain transactions.

But it also goes the other way - at any given time, miners can choose to limit their production of block space in order to impose costs upon transactors. However, this involves a bit of race-to-the-bottom game theory because the nature of mining is such that it disincentivizes cartelization - even if a large percentage of miners agree to self impost a lower block size cap, if this means they're "leaving money on the table" by not including some transaction fees, then a more efficient miner may come along and break the cartel in order to collect those fees.

Sustainable Thermodynamic Security

Currently, miners are earning roughly $300,000 per block. Each block contains roughly 3,000 transactions. As such, to sustain the current level of security spend without any block subsidy (newly created bitcoin) then each transaction would need to pay a fee of $100.

It would be great to set a block size adjustment based upon fees, though one problem is that it's possible for miners to stuff blocks with their own privately mined transactions and thus pay high fees to themselves, which could skew such calculations. Though you could argue that miners can do the same thing with stuffing blocks to raise the floor on fee rates. We haven't seen much evidence of this recently. In 2024 I wrote some analysis tools to search for privately mined transactions and found practically none, but going forward if we think there is fishy activity we now have the ability to easily find it. Here's my report on that topic:

A Block Space Adjustment Mechanism

Bitcoin's consensus rules include a difficulty adjustment mechanism for the required proof of work. Why?

- It's a feedback mechanism to smooth out how much the system is paying for thermodynamic security

- Energy costs can fluctuate

- Technological advancements can make energy generation more efficient

- Bitcoin's exchange rate is volatile and Bitcoin as a system has no knowledge of its own exchange rate

Difficulty adjustment is a critical piece of stabilizing Bitcoin's thermodynamic security. I posit that, in the very long run, a block space adjustment is similarly important.

I don't have a specific proposal at this time but it seems like a dynamic block size adjustment algorithm would need to do the following over some period of time similar to the difficulty adjustment algorithm:

- If more than 99% the block space for the past adjustment period is consumed, analyze the fee market and block space usage to see if it's safe to bump up block space by some conservative amount that's limited by other constraints used to roughly measure the cost of node operation and keep the resource cost bounded by various factors of technological growth. In other words, allow the block size to grow as long as it doesn't upset the balance of power and doesn't negatively impact the block space market.

- If less than 99% of the block space for the past adjustment period is consumed then check if we have fallen off the cliff for having a sustainable market for block space and reduce the allowed block space by the amount that was not consumed.

Why 99% rather than 100%? Because about 0.25% of blocks are empty (as of the past 100,000 blocks) due to being found too quickly after the previous block. This frequency has been decreasing over the years as transaction and block propagation technology continues to improve. I wrote about this phenomenon several years ago:

If blocks became significantly larger, this could increase the rate of empty blocks, and having a high threshold on the block space adjustment algorithm would be another way to keep it in check.

Activation Process

I've published research previously that argued Bitcoin has hard forked in the past, though it was when the network was small and the actual trigger of the fork happened years after the protocol was changed.

the time between the v0.3.6 release and the first spend of an OP_NOP redeem script, thus triggering a hard fork condition for older clients, was 18 months.

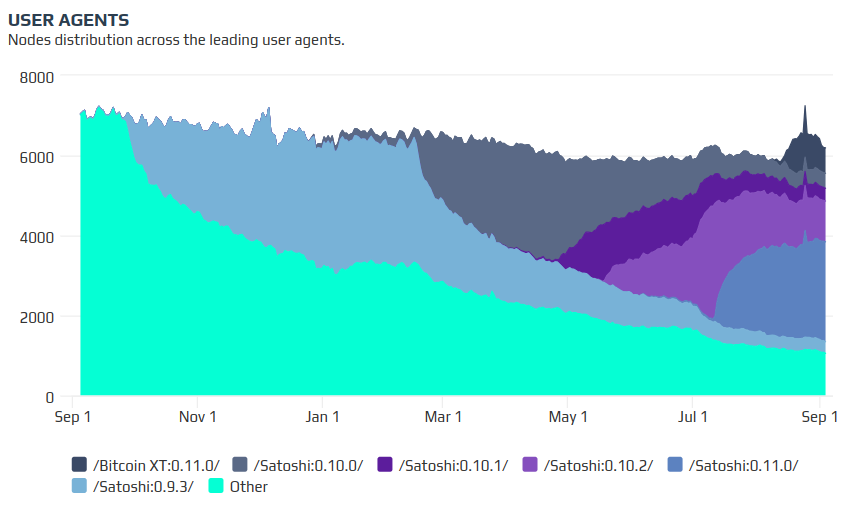

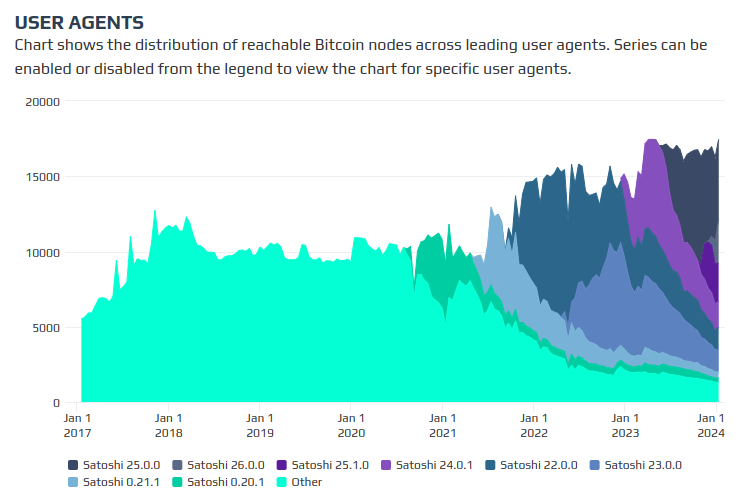

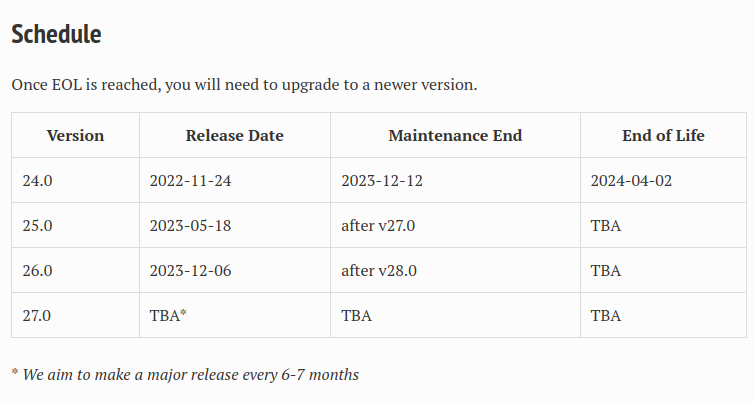

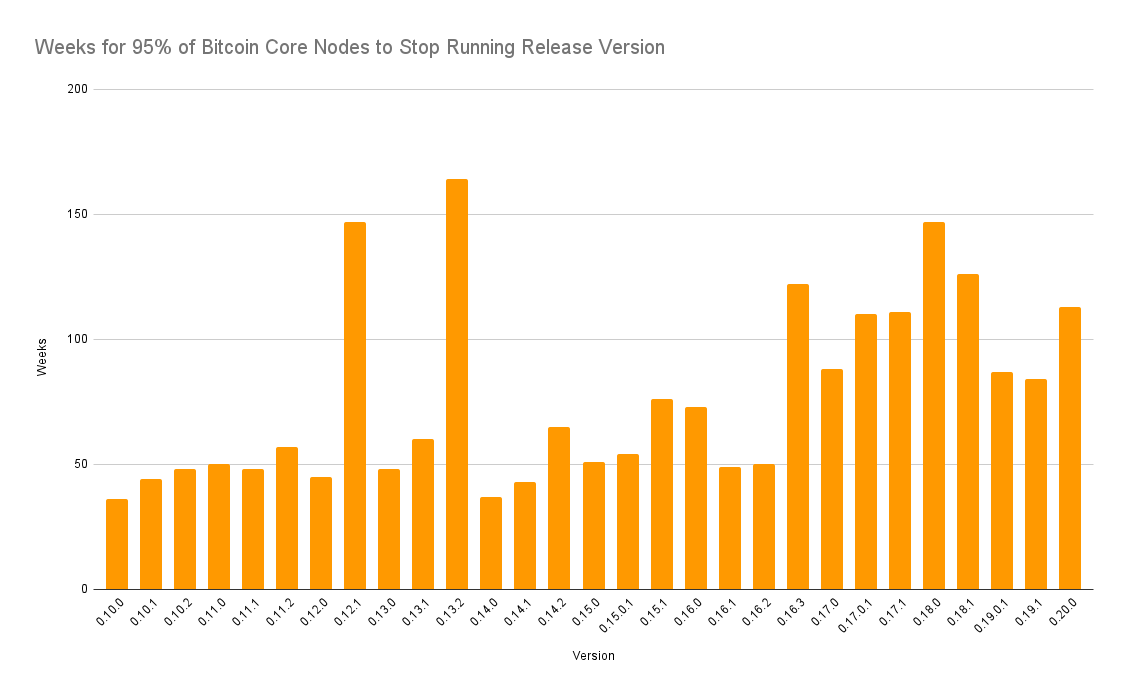

I have a theory based upon the above research that (uncontroversial) hard forks are much less problematic if their activation is set far enough in the future. We have 7 years of Bitcoin node user agent data from Bitnodes that we can analyze to draw some rough conclusions around the software update lifecycle. In short, it looks like roughly 90% of node operators tend to update their software clients within 2 years of a given release.

Note that in BIP-103, Pieter Wuille stated:

Waiting 1.5 years before the hard fork takes place should provide ample time to minimize the risk of a hard fork, if found uncontroversial.

It's probably not a coincidence that 1.5 years also happens to be the same amount of time that the Bitcoin Core project promises to maintain a given release with security patches.

Point being: while we like to talk about how you can theoretically run any version of Bitcoin Core and still sync with the rest of the network, that doesn't mean it's a good idea. Releases that are more than 2 years old are likely to contain unpatched vulnerabilities.

From this chart you can see that 3 years after a given node release, over 95% of operators tend to have upgraded.

Going Forward

As stated at the beginning of this essay, there's no rush to implement any changes - this is a very long term problem and we can take our sweet time searching for an optimal solution. Perhaps we'll never find consensus for a solution that makes everyone happy, in which case I'm not claiming that Bitcoin will fail, but we should expect that the nature of how it's used and by whom will change.

I think there is general agreement that Bitcoin's long-term thermodynamic security is an important issue that's currently up in the air with regard to sustainability. Some have suggested we may need long-tail supply inflation to ensure rewards for miners. Many of us hope that's not necessary, and Satoshi's vision of transaction fees replacing block subsidy will come to pass. One of my primary points to take away from this essay is that I believe other solutions exist that can help ensure a more sustainable market for block space without needing to inflate the monetary supply.

"Bitcoin will need tail emission to pay for thermodynamic security."

— Jameson Lopp (@lopp) December 4, 2024

Doubtful.

1. It's a non-issue until BTC goes for 4 years without doubling in price.

2. Other levers can achieve similar results, such as raising minimum transaction fees or adjusting block space downward.

I am a sovereignty maximalist; as such I'm not a huge fan of the trend we've seen over the past year. Never before has been seen all-time high exchange rates with an empty mempool. I think the explanation for this is quite simple - a ton of demand is only happening through ETFs and large custodians, thus reducing demand for block space.

An empty mempool is a sign that sovereign usage of Bitcoin is extremely low.

— Jameson Lopp (@lopp) February 1, 2025

This trend becomes additionally concerning when you consider the perspective and incentives of aforementioned trusted third parties.

The folks who are focused on TradFi adoption of Bitcoin don't care about improving the protocol and scaling the network because they don't care about self custody.

— Jameson Lopp (@lopp) September 21, 2024

The next battle for the future of Bitcoin is brewing.

I intend to think deeply about this topic for the forseeable future in the hopes of coming up with a proposal; if you find this interesting and have ideas to contribute, please reach out so that we can collaborate!